Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

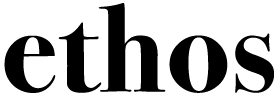

These days, Buckminster Fuller is a name that may not be immediately recognizable, but his work has had a significant impact on our world, reshaping how we view and solve problems.

In 1997, long before iPhones were ubiquitous, Apple’s co-founder Steve Jobs was gearing up for something big. It wasn’t the new Powermacintosh G3 computer Apple was about to launch, or the company’s 20th anniversary. It was a paradigm shift in how we view technology, and it was the focus of the now-legendary “Think Different” campaign, which stated,

“Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules and they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify, or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

Narrated by actor Richard Dreyfuss, the Apple ad shows footage of changemakers most of us are familiar with: Martin Luther King, Jr., Albert Einstein, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Muhammad Ali, Mahatma Gandhi, and Jim Henson (with Kermit the Frog), among others. Sandwiched in that ad, though, was someone much less familiar but no less significant: R. Buckminster Fuller.

Nearly 20 years before the ad campaign ran, Jobs had his only meeting with Fuller, then age 85, in what was supposed to be a clip for a cable show. As the story goes, Fuller was skeptical about the Apple II computer, thinking it a toy. But Fuller had spent most of his life taking the opposite approach to novel inventions: anything was possible.

Perhaps he was pulling Jobs’ leg, or perhaps, as he moved closer toward his final days, even one of the most prolific creative minds in recent history met a concept so radical that even he couldn’t quite understand it. Given the Technological Age seems to be moving faster than most of us can keep up with even now, 40-plus years later, it’s not implausible.

But while the polymath may have been thrown off by a desktop computer, Fuller was anything but a Luddite. His work, which is carried on today by the Buckminster Fuller Institute, is often described as a search for practical solutions to real-world problems. Fuller was deeply concerned about the state of the environment and the impact that human activities were having. He believed that by using science and technology, we could create a more sustainable future.

Fuller worked tirelessly to benefit humankind; he counts dozens of inventions to his name, published more than 30 books in his 87 years, and coined or popularized terms such as “Spaceship Earth” (a favorite of soapmaker Emmanuel Bronner), “Dymaxion” (e.g., Dymaxion house, Dymaxion car, Dymaxion map), “ephemeralization”, “synergetics”, and “tensegrity,” among others.

Fuller’s work has had a profound impact on the fields of architecture and design, as well as popular culture. His innovative ideas about structure, efficiency, and sustainability have inspired generations of futurists, artists, designers, and more.

Who was Buckminster Fuller?

Born in 1895 in Milton, Massachusetts, Richard Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller was the second of four children.

Fuller attended Harvard University (but was expelled twice, once for “conduct unbecoming a Harvard student” and later for failing to pay tuition). Despite this setback, he would never stop learning and go on to become a visionary inventor, architect, engineer, and futurist who believed that science and technology could be used to improve the lives of people around the globe. His work spanned many disciplines, and his ideas were often ahead of their time.

Fuller’s radical ideas began to pick up momentum after a profound spiritual experience that pulled him out of a deep depression following the death of his four-year-old daughter from spinal meningitis in 1922.

Several years later, he described an experience where he felt as if he was floating several feet off the ground inside a white light. He recounted a voice telling him: “From now on you need never await temporal attestation to your thought. You think the truth. You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the Universe. Your significance will remain forever obscure to you, but you may assume that you are fulfilling your role if you apply yourself to converting your experiences to the highest advantage of others.”

That experience forced a wholesale re-examination of his life that Fuller described from then on as “an experiment, to find what a single individual could contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity.”

And experiment he did.

Influence on architecture and design

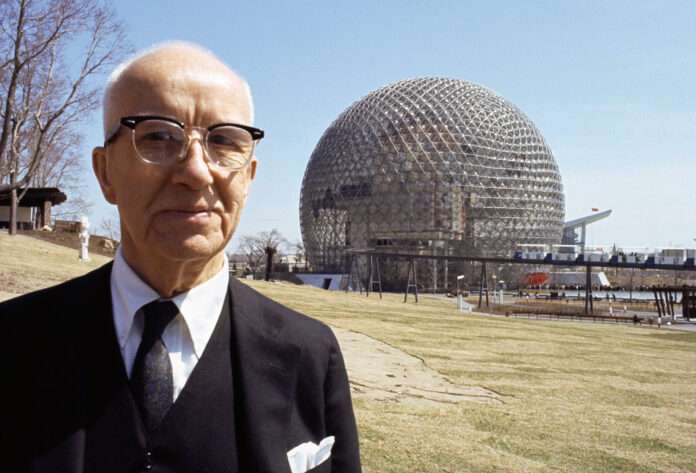

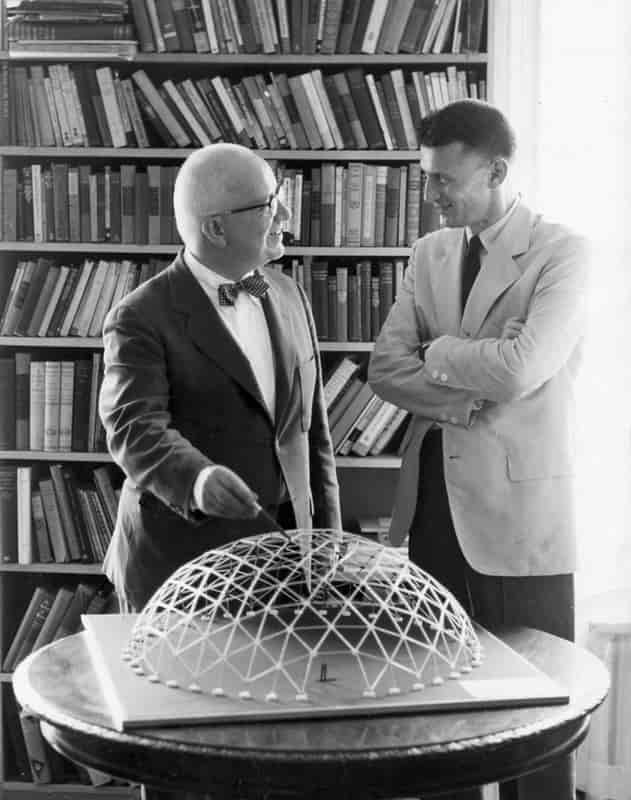

Fuller invented many things during his life, but the one that has stood the longest test of time is the geodesic dome, a structure made up of interconnected triangles. The design structure is incredibly strong and efficient (he would later create his own geometric system based on these triangles). The dome is now used in all manner of structures, from sports arenas to greenhouses and homes.

The dome was inspired by Fuller’s study of nature; he believed that the dome could be used to solve many problems, from housing shortages to environmental degradation.

Fuller also believed that buildings should be designed to be as efficient as possible, using the least amount of material to cover the greatest amount of space. This led to the development of lightweight structures, including the domes.

“Looking back over the 12 years of our collaboration and friendship there are many papers that could be written on the insights that Bucky offered,” British architect Norman Foster wrote of his friendship with Fuller. “But perhaps the themes of shelter, energy and the environment — which go to the heart of contemporary architecture — best reflect Bucky’s inheritance and his importance to me as a mentor.”

Fuller also designed the Dymaxion Car, a three-wheeled vehicle that was intended to be energy-efficient and aerodynamic. The car was never mass-produced following an accident that involved the death of the driver, but it was a significant achievement in automotive design, paving the way for modern cars like the three-wheeled solar-powered Aptera.

Fuller’s work also inspired the development of prefabricated building systems, which can be mass-produced and easily transported. This approach to building has been used in emergency housing to high-end residential and commercial construction.

Influence on environmentalism

Fuller had a deep understanding of the likelihood of a maxed-out future on Earth and the pressures modern society was putting on the planet; he imagined that one day we would live in massive ocean settlements and balloon-like floating communities in the clouds as a result of our mismanagement of Earth’s resources.

He believed that science and technology could be used to create a more sustainable future with his ideas and inventions always pointed toward that goal.

“We are not going to be able to operate our Spaceship Earth successfully nor for much longer unless we see it as a whole spaceship and our fate as common,” Fuller famously said. “It has to be everybody or nobody.”

This ethos reflects his belief that we are all connected and that we must work together to create a sustainable future. He believed that we must see the earth as a whole system and recognize the impact that our actions have on it.

His ideas about efficiency, lightweight construction, and renewable energy have influenced the development of sustainable building practices and renewable energy technologies.

Fuller’s philosophy of comprehensive thinking, in which he sought to integrate science, art, and philosophy to solve problems, continues to be relevant in the 21st century. As we face the challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and social inequality, Fuller’s work is a reminder that we need to take a holistic approach to problem-solving and work together to create a better future.

As Fuller himself once said, “You never change things by fighting against the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

Fuller’s philosophy

Fuller’s personal philosophy ran deep and included a number of self-disciplines, including critical thinking and seeing oneself as an experiment as he discovered after his spiritual awakening.

“At the outset of my resolve not only to do my own thinking but to keep that thinking concerned only with directly experienced evidence, I resolved to abandon completely all that I ever had been taught to believe,” he wrote in his 1981 book, Critical Path.

His philosophical views also extended to politics and foreshadowed much of the current dysfunction in the two-party political system. Also from Critical Path,

“Few realize that political action offers little solution to the world’s major problems. Few understand that the elite have created political parties in order to prevent real change from ever taking place. The political arena is merely the ‘sty’ in which two or more mutually hostile agencies, created by the same hidden hand, get the chance to pummel one another. As alternative researcher Juri Lina so brilliantly put it: When the left wing Freemason is finished, the right-wing Freemason takes over The point has been emphasized by many an insider: The elementary principle of all deception is to attract the enemy’s attention to what you wish him to see and to distract his attention from what you so not wish him to see – General Sir Archibald Wavel The world’s power structures have always ‘divided to conquer’ and have always ‘kept divided to keep conquered.’ As a consequence the power structure has so divided humanity – not only into special function categories but into religious and language and color categories – that individual humans are now helplessly inarticulate in the face of the present crisis. They consider their political representation to be completely corrupted, therefore, they feel almost utterly helpless.”

But Fuller remained ever the optimist, a hopeful champion of the human spirit and its eventual, unavoidable evolution. “I live on Earth at present, and I don’t know what I am,” he said. “I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing — a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process — an integral function of the universe.”

In 1975, Fuller gave a series of lectures entitled Everything I Know that aimed to synthesize his life’s work and experience.

Here are five of his most enduring life lessons:

1. Humans are not separate from nature

This philosophy endures throughout Fuller’s creations, books, and lectures. He was constantly measuring his work against his place in the universe, our place in the universe, and, more often, our place on the world and its impact on everything and everyone else. Biomimicry is the system of solving human problems by mimicking solutions in nature — airplanes designed to fly like birds, burrs that inspired Velcro, etc. Fuller constantly looked to nature for inspirations such as these and found answers to a range of problems.

2. Less is more

Like his efficient geodesic dome, Fuller envisioned a world where resource use was minimal. He called this “doing more with less” or “ephemeralization” and it’s a philosophy that is more true now than ever as the climate crisis looms and resources face unprecedented threats.

3. Learn from your mistakes

It’s a lesson we hear a lot as children, but less so as adults, perhaps, as our brains age and neuroplasticity wanes, we see our own mistakes less (read: we think we’re always right). Fuller lived by the opposite philosophy and looked for the lessons in his mistakes but without dwelling on them or stressing over them. He said he’d rather invest his time in “technological effectiveness” instead.

4. See yourself as an experiment

Fuller struggled throughout his life emotionally and financially. But he always looked at his life as an experiment — as unique as the universe itself. He spent every second he could exploring and experimenting and it led to hundreds of inventions and countless more ideas.

5. Be in service

While his own life was very much an experiment, Fuller’s work was always in service to the greater good aimed at solving the world’s biggest problems. By serving others, he said his own needs would also be met and never waivered from that commitment.

Related on Ethos: