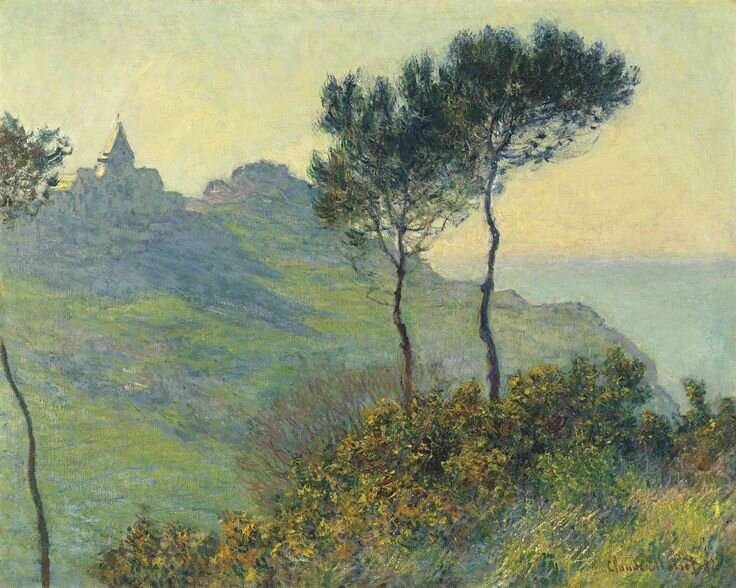

Climate change is taking its toll on a classic art destination — the inspiration behind Monet’s L’Église de Varengeville, soleil couchant.

The Saint-Valery church in Monet’s 1882 painting, which sold at auction in 2014 for more than £5 million, is located in Varengeville-Sur-Mer in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of France.

Eglise de Varengeville, soleil couchant and the Saint-Valery church helped Monet earn his status as a leading landscape painter. “Monet’s enthusiasm for the views he found in Normandy may have influenced his decision, the following year, to rent a house and land at Giverny; this would become his base for the rest of his life, and would allow him to sally forth on his various painterly campaigns, especially in his locality,” Christie’s, which sold the painting, explains.

“Gradually, [Money] would cultivate surroundings at Giverny, including his legendary gardens, which allowed him to find a constant supply of subject matter on his own doorstep. However, it is a mark of the importance of the views of Varengeville that he would return there again at the end of the following decade,” Christie’s notes.

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, the region was a destination for artists. Today, it’s a tourist destination, bringing tens of thousands of visitors a year.

Climate change in Normandy

Experts say the famed 11th-century Romanesque and mixed architecture structure is now facing certain demise as sea levels rise due to climate change. The cliffs are made of chalk, sand, and clay, making them more vulnerable to erosion. At the time when Monet painted L’Église de Varengeville, soleil couchant, the spot where the church stands was half-a-mile inland; now it is ten meters from a parcel of land already sliding toward a cliffside receding by a meter per year.

Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Corot were also drawn to Varengeville — and eventually the Cubist artist Georges Braque, who later became a resident in the village “and since 1963 lies buried in the cemetery adjacent to the church,” says the Art Newspaper. Braque’s grave, along with his wife’s and servant’s, will also be lost to coastal erosion.

According to a 2019 study published by the American Academy of Sciences, rising global temperatures could increase ocean levels by two meters by 2100, putting coastal regions around the world in jeopardy. In Normandy, flooding will increase, with World War II battle sites lost as the town of Carentan predicted to be underwater.

The nearby Musée du Débarquement at Utah Beach in Sainte-Marie-du-Mont (Manche) sits on the site of the first beach stormed in Normandy in 1944. But, like the cliffs where Monet’s famous church sits, the dunes where the museum sits are also progressively eroding.

Currently, the village adds around 7,000 cubic meters of sand to the beach every two years to help prevent erosion. It also plants beachgrass to keep the dune in place, but experts say this may not be enough.

Rising temperatures are changing much of France’s landscape. France’s wine industry has begun seeing the flavor profile of grapes change. Scientists and the French government are looking at new grape varietals as a result.

Vineyards across the country’s wine-producing regions are moving to more sustainable growing methods. In Bordeaux — the wine capital of the world — 100 percent of vineyards will be certified organic, biodynamic, or sustainable, or in transition, by 2025. Already 65 percent of winemakers in the region meet the criteria.

But transitioning the wine region to sustainable growing methods won’t stop the impact of climate change on France. Global shifts are needed, warn the world’s leading climate organizations. Without significant efforts to reduce heat-trapping emissions across transportation, energy, and agriculture, experts say the planet will surpass the 1.5° C Paris Agreement threshold, pushing the planet into extreme weather events including increased droughts, floods, and fires.

For the Northern France coastlines, any efforts to thwart climate change’s impacts may already be too late. “The changes here around are huge. We moved from around three major cliff crash events per year to now a dozen crashes,” captain Stéphane Dodivers told EuroNews last year.

“And we are just talking about this 30km part of the Normandy coastline. Personally, I feel very sad about this, because it means that the cliffs will have another face and, for certain in a few decades the arcs of Etretat won’t exist any longer,” Dodivers said.

L’Église de Varengeville, soleil couchant

According to Christie’s, Monet was fascinated with the landscape in Normandy. “I can’t help myself from being seduced by these admirable cliffs,” he once said.

“The year before he painted Eglise de Varengeville, soleil couchant, he had been enchanted by the views at Fécamp; the year after, he would tackle one of the icons of the French landscape, Etretat, which had previously been painted by a number of artists including another of his mentors, and indeed a witness at his wedding, Gustave Courbet,” Christie’s explains.

“It has been suggested that Monet’s return to Normandy in the early 1880s was in part a reaction to Courbet’s legacy: he had died in 1877, but his Normandy landscapes and seascapes had become significant parts of the French avant-garde canon, tapping into a vision of France during that troubled period following its defeat during the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent revolutionary chaos.”

The church, now an historical monument, has seen €1.5 million in repairs in recent years from upgrades to the roof, beams, walls, and foundation. But according to Arnaud Gruet, a local councilor, “It will eventually slide into the abyss, even collapse piece by piece and fall into the sea,” he says.

Despite efforts to combat coastal erosion and reinforce the structure, experts say there’s little hope for the church on the cliffs of the Seine-Maritime Department.

Some experts are suggesting relocating Saint-Valery — literally disassembling it brick by brick and rebuilding it further inland. Another idea being floated is moving it in its entirety on rails and dollies, but concerns about the stability of the land to be able to endure the heavy equipment make it an unlikely option.

But, increasingly, it seems Saint-Valery’s future hinges on the same circumstance that gave it such a storied history: luck. Monet stumbled on the church quite by accident; he was on a leisurely walk along the coast.

Related on Ethos: