There’s an urgent shift needed on our planet, and our food system plays a critical role in fixing the climate crisis. It can feel like progress isn’t happening fast enough but take it from a longtime “picky eater” —we’ve come farther than you may think. Turns out the long, slow, and often nostalgic shifts to our food system signal a whole lot of progress.

There’s a saying I’ve long loved. It’s attributed to the writer C.S. Lewis, but its origins aren’t totally clear. It goes something like this: day by day, nothing changes, but when we look back, everything is different. I thought of this recently as I walked past a payphone.

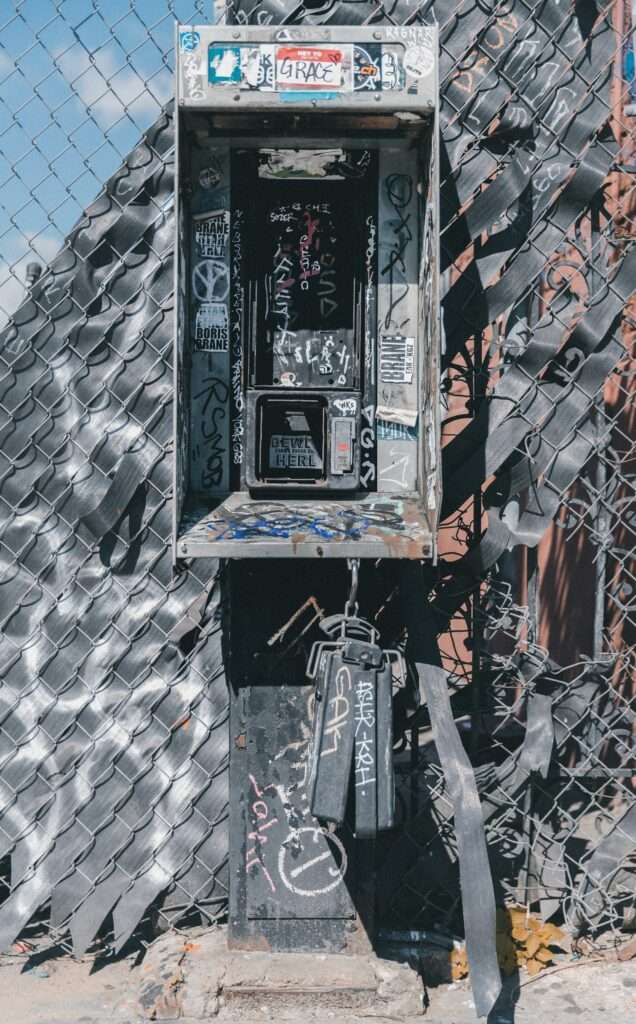

The payphone is a token relic of yesteryear — an apt metaphor for the strangeness of going from necessity to irrelevance. Payphones have found new relevance by way of memes and art galleries. This phone in particular fit the bill of tattered relic — the phone handle had been pulled off the cord, the booth was covered in graffiti, stickers, trash, and decades of grime. I wondered if it was an art project — street art like that is not uncommon in Los Angeles.

What do kids think of it, I thought? Why was this one left behind? Had it been forgotten? Left intentionally as a reminder of the passage of time? Certainly, just a few decades ago, there were payphones like this on every corner. Now there are next to one. Why did this one remain?

It’s an apt metaphor for lots of things, especially our food system. It’s in a state of upheaval now, from the unthinkable amounts of food waste to the emissions produced by meat and dairy, the clearcutting for animal feed and palm oil, and the ultraprocessed foodstuffs.

Back when payphones were still a thing and Impossible Burgers was quite literally a most impossible future, I stopped eating meat, which was a bit like using one of those giant mobile phones that were as heavy as irons and never really worked. I didn’t have a great aha moment that turned me off from animal products. There was no PETA video or fur protest, no animal being tortured or slaughtered in front of me to seal the deal. My story is rather mundane, truth be told.

‘Picky eater’

For as long as I can remember, I was dubbed a “picky” eater, which I most certainly was, but only when it came to the foods most people loved. It would be years, two decades, really, before I made the connection — before I realized that I wasn’t picky at all when it came to fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, whole grains, or beans. The foods I didn’t like were typically foods other kids ate instead of finishing their vegetables: meat, cheese, milk, butter, and eggs. Seriously, what kid doesn’t love chocolate milk or cheese?

For me, it was the opposite. I recall revelatory moments eating my first heirloom tomato. I couldn’t have been more than five years old. It was as if I felt my tastebuds come alive for the very first time. But I felt this way about other fresh fruits and vegetables, too. I remember my impatience in waiting for the corn and beans in our garden to grow so I could eat them until my belly hurt. Those first summer peaches were a fixation. My first artichoke was as near a religious experience as I’d ever had even to this day — peeling those thistled leaves one at a time and scraping their earthy goodness with my young teeth was like a meditation. This was food, I was sure. And I was hooked.

In my early teens, I toyed with vegetarianism; I wouldn’t hear the word “vegan” for several more years. By then I’d learned to eat better in a world filled mostly with foods I couldn’t stand. Peanut butter still holds a special place in my heart after sustaining me for all those years. But without the wide availability of options we have today and parents too busy to experiment on my behalf, I was forced back to eating foods that gave me the ickiest feeling every time I took a bite.

Despite not knowing there was a word for what I was feeling, my conscience gnawed at me. Eating animals was unethical; it was something that just felt entirely true to me. It was undeniable. It still is.

When I was 21, I spent six weeks backpacking through Australia. We cooked a lot from our small camp stove, freeze-dried soups, and the like. But when we were in the cities between parks for a night or two, typically the Tasmanian capital Hobart, we’d find a restaurant. On one of those occasions, we found a small hole-in-the-wall restaurant focused on fresh, local ingredients. It was farm-to-table before that was a thing. It blew my mind — a refreshing break from the fried fish and chips at every other place. I remember my first taste of a bright, green pesto, and salads with leaves I’d never seen before. We want back several more times when laying over in Hobart.

Another stop on that pivotal tour of the outback was found at a bed and breakfast with the most delightful yet simple vegetable soup. I had never tasted something so fresh and so satisfying. These delicious meals came to mind at another stop as I was eating a slice of pizza, when I suddenly found myself incapable of taking another bite. I’d always struggled to like cheese, but like most anyone, I enjoyed pizza. Not that day though. It was a reckoning of sorts. I could never go back to the way things had been.

Years later on a trip to Paris, I’d have a similar sense of food awakening with a strawberry from a local farmers market. It’s possible food just tastes better while traveling, I told myself. But I think there’s something more to it. In Australia, perhaps it was that these meals weren’t deep-fried like so many of the offerings at the time. But also, at 21, I hadn’t eaten outside of my little Rust Belt town where the food was mediocre at best. And by the time I made it to France, I was years into a healthy plant-based diet. What I tasted there was an organic berry very much different than our American berries. These farming methods are as critical to our food experiences as they are to the health of our soil and our food system. It’s something we don’t talk about nearly enough.

The only problem with these vacation foods was that it was incredibly difficult to forego animal products at every meal back then. I grew up in Western Pennsylvania where meat and cheese were staples. Restaurants had yet to embrace vegetables beyond the garnish, let alone an entire meal made from them. I sustained myself on coffee, French fries, and iceberg lettuce salads, for as long as possible, which was not very long at all. It was quite literally a choice between eating animals and starving most days. For me, it was an unpleasant mix — oscillating between the two and filling the gaps with the ersatz world of junk food. And I can’t help but wonder how many other “picky eaters” are actually food lovers just being fed the wrong food.

Finding a new way of eating

Recent research has found there may be a genetic link predisposing us to a plant-based diet. The researchers identified three genes that influence brain function and fat metabolism. More than 30 other genes were also connected to a greater likelihood of adopting a vegan or vegetarian diet. And scores of research point to the benefits of adopting a plant-forward diet for optimal health.

As I longed for those ripe, juicy summer tomatoes, and the garden vegetables I loved as a child, I knew there was another way. There had to be. And so, I took a job working at my local health food store in its small vegetarian café. I had some experience cooking (a story for another time), but now I was going to learn a lot more. And I did.

We made lentil loaf and tofu burgers, soups, stews, and chilis in that kitchen; I even learned how to work a juicer and drank so much carrot juice it turned my skin orange (word to the wise). There was a vegetable soup reminiscent of the revelation I’d tasted Down Under.

The front of the store sold all kinds of healthy foods like beans you couldn’t find at conventional supermarkets, tahini paste, miso, and nutritional yeast. Back then, if you wanted tofu, you had to fish it out of a big plastic bucket where blocks of tofu floated in ice-cold water. I don’t recall where the tofu was made but it had to be within a few hours or so of my town.

Vegenaise existed back then, and yes, people still mispronounced it then, too. There were two types of vegan milk: soy and rice. Edensoy was my favorite, but it tasted nothing like the vegan milk we have today. It was made the Japanese way, malty and brown and delicious when served cold over ice. Rice milk had a bitter aftertaste and was too thin for me. But when Rice Dream made frozen desserts out of it, we all flocked to the freezer first thing on payday to get the chocolate-covered treats on sticks like children chasing the last ice cream truck of summer.

I remember one chocolate company made a vegan candy bar with green tea and cocoa butter instead of chocolate — like white chocolate, I suppose. It had crisped rice in it, and I don’t know if it’s me romanticizing the memory or not, but I swear it was the best treat I’d ever had vegan or not.

The other options were typically made from carob, and I’m still a fan even though today we now have delicious vegan chocolate bars from Hershey’s, Cadbury, and Nestlé or truffles and treats that rival the “real” stuff. If someone had told me back then that in just a few decades the best chocolates in the world would be completely dairy-free and delivered right to my door, I’d have thought they’d lost their mind.

Back then we had vegan cheese options if you can call whatever those things were then cheese. They were waxy, oily slices and wedges, or weirder yet, dairy-free cheese that also had casein in it to help it melt. I’m not sure I’ll ever figure that one out, but several brands did it.

One thing I did know for sure was that I didn’t like any of it. I came to good terms with being cheeseless. Nutritional yeast can do some pretty heavy lifting and is still my preferred mac and cheese sauce (use a bit of the warm pasta water, paprika, a dash of dijon or olive oil, and as much nutritional yeast as you want — the more the better — and enjoy).

We had some vegan meat options then, too. Boca Burgers were all the rage; they sizzled and smelled like fast food burgers as we cooked them on the café grill. They were too realistic for me then, but by today’s standards, they’d never rival Beyond or Impossible Burgers. Today if I want something “meaty” I usually opt for seitan, just as I did back then.

The future of food

Lately, I’ve been thinking about those early vegan foods a lot. I enjoy the modern vegan versions of all of them, particularly oat milk in my coffee and the occasional chicken sandwich — although my chicken of choice is made from mushrooms. There were many experiences that shaped how I eat today, which are mostly whole foods-based and macrobiotic with a very Mediterranean influence. Give me fresh salads, veggies, beans, olives, and nuts over vegan nuggets any day.

Even though I have no interest in trying them myself, I love watching many of my contemporaries run to their local McDonald’s, Burger King, Taco Bell, or KFC to try the new vegan options after decades of waiting. I remember the thrill my veggie friends and I would get going to McDonald’s and ordering the burger minus the patty — it makes me laugh just thinking about that soggy bun filled with pickles as something satisfying. What I would have given back then for just a bite of a McPlant.

But here we are, watching the slow hands of time as progress is indeed being made. There are fast food burgers, and Ikea sells vegan hot dogs for less than $1; there are vegan pizza options at major chains, and so many sweets, treats, and dairy-free drinks at coffee shops, that it’s now impossible to try them all. That’s not even including all of the progress being made in the cultivated meat sector, the precision fermentation, the biomass fermentation, and the techniques we still haven’t developed yet that are sure to gobsmack us with human ingenuity.

When I first stopped eating meat, the best “meat” option we really had was to crumble up tofu and pour in spice packets from a company called Fantastic Foods. They’re no longer around; it’s a sign of progress, of course, that instead of powdery packets dumped onto tofu, people are opting for any of the myriad pre-seasoned options across refrigerator and freezer aisles, delivery apps, and more.

I have to ask myself: twenty years from now, will I be nostalgic for Beyond Burgers like I am thinking about old seasoning blends to zhuzh up tofu? What comes next in our race to clean up our food system? Because that’s what this is about, right? Fixing our food system so we can all live long enough to eat more food? In this context, we should all be picky easters.

Early food system innovations aren’t all that old — Tang, Spam, and all the rest of it — were positioned as conveniences for the busy homemaker in the 1950s. Before that, most everything was made from scratch. These innovations promised freedom for housewives. But more than anything, they were profit-driven new revenue streams for the corporations who fed us (and covered the planet in plastic). And that’s not to say profits don’t belong in our food system, they do, certainly. But these days, corporations have some problems to fix that go beyond just freeing up a few hours for tired housewives.

That’s what scientists are telling us. It’s not about teenage ethics (although let’s be real, everything kind of is). Curbing meat and dairy consumption is a matter of life and death — both for our health and the planet. We’ve already come so far. We’ve already seen more innovation than a hungry young teenage vegan could ever have imagined. And I think the best is yet to come. It doesn’t feel inaccurate to suggest that factory farming and ultraprocessed foods made from farmed oils that took down giant swaths of rainforest, will soon be just like that relic payphone — a moment out of time lost in modernity. A few may still hold a space in the labyrinthian aisles of the supermarkets, but long past their heyday.

I’m old enough to remember using payphones. They were staples in my youth: check-ins with friends late to meet at our scheduled rendezvous point, or quick calls home asking if I could stay out just a little longer. Nowadays it’s absurd to think about using one for any reason other than nostalgia or emergency. The computer in my pocket is better in every single way.

And just like that tattered payphone stopped me in my tracks on the street, I’m certain the modern inefficiencies in our food system will soon seem just as awkward and out of place, surpassed by technology that’s better in ways we can’t yet even imagine. It’s a bit more complicated to remove a system that’s built to feed eight billion people three times a day than a payphone, but like with anything, we’ll find a way. Because like that Lewis quote says, when we look back, everything is always different.

Related on Ethos: